A second post for this week? Crazy right? After a look at the Narrative in relation to player interaction in Dark Souls that can be found here, I will be looking at Ludonarrative Dissonance. Ludonarrative Dissonance refers to the conflicting approach that can be found in Video Games between Gameplay choices (ludic) and Narrative choices. This term was first coined in a blog post by Clint Hocking called Ludonarrative Dissonance in Bioshock. Feel free to give it a read before reading this post as I will be referencing it heavily.

I myself had always been under the acceptance that a Game is a Game, meant to be enjoyed through gameplay and that it’s narrative can come second. Even when these two features of the game clashed I never really thought about it. Having read Hocking’s post I now seem to understand the importance of the term ‘Ludonarrative Dissonance’.

Looking strictly at Bioshock with relation to Hocking’s post for starters. I have only played through about half of the original Bioshock so this might seem biased to the critique. The game seems to “suffer from a powerful dissonance between what it is about as a game, and what it is about as a story”. It does this by “throwing the narrative and ludic elements of the work into opposition”.

Bioshock as a whole is an examination and criticism of ‘Randian Objectivism’. This refers to the practice that whatever helps you get ahead is morally the correct choice. During gameplay the player is given the choice to either save or harvest characters called ‘Little Sisters’. These ‘Little Sisters’ are used to gain upgrade points in the form of Adam, which is used to upgrade your unnatural powers. This enforces the Randian way of thinking as harvesting the ‘Little Sisters’ rewards the player with more Adam than saving them would.

Narratively, the player is given no such choice. You MUST help someone, this being Atlas, to progress through the game. This directly opposes the Randian way of thinking, since the gameplay shows that you can have the choice to not help anyone and do what is best for you, the player is more aligned with the game’s antagonist ‘Andrew Ryan’. So why should we oppose him if our philosophical beliefs align?

The answer is: Because the narrative says so.

The way I would and did go, and most others would go, is to accept that it’s a game and since the mechanics are great they’ll overlook the break that is the narrative forcing them to do something out of character. Hocking suggests that this is a mocking of the player for accepting the weakness of the medium.

As I stated earlier, I personally don’t mind when these two features of Video Games don’t align properly. If I wanted a compelling story without the fun of going through it myself I would watch a movie. Or if I wanted to play through a game while focusing on gameplay alone I’d play Tetris or Dark Souls (an interesting comparison but anyway).

Dark Souls Cover Art

Tetris 99 Cover Art

Regardless of my feelings towards this blog post and it’s contents. I will say that this kind of term, that being ‘Ludonarrative Dissonance’, is important for games criticism. Being able to point out the shortcomings of a highly narrative driven game such as Bioshock is important. Bioshock happens to be a loose fit I would say as both elements, Narrative and Gameplay, are fantastic from my experience and you can enjoy it for both while not being unimmersed while playing. Being able to describe the difference in Gameplay and Narrative in a single statement is very important as it lets whoever is critiquing a game get the point across easily without threat of confusion.

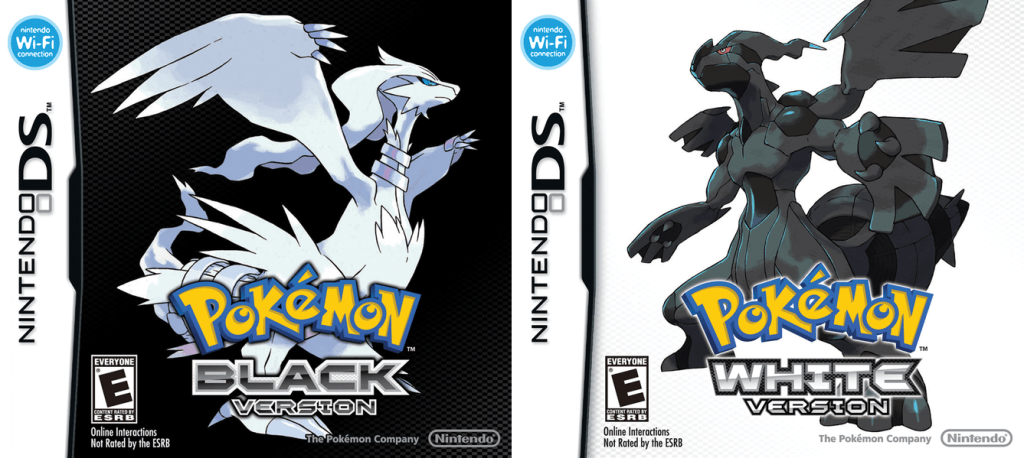

I can say that I have run into this Ludonarrative Dissonance before. In Pokemon of all places. In Pokemon Black and White, the first instalments of the Fifth Generation Pokemon games, presented a narrative that greatly opposed the core gameplay of the series.

The Player is presented a philosophical question. The question being “Is training and battling Pokemon in the way we have morally right?”. This is posed to the player by the character ‘N’, a mysterious person working with the game’s villainous team, ‘Team Plasma’. For most of the game N and Team Plasma suggest to the player and other characters about the moral correctness of battling Pokemon. With questions like; “What if Pokemon don’t want to battle?”, “What if Pokemon don’t want to come with you?” and “Would you feel comfortable being sucked into a ball and live there for most of your life?” it was hard not to think about these questions and what it relates to in real life. What if we were chicken fighting instead? Or Dog racing even? It definitely challenges the players moral compass.

Official Artwork for N with a Legendary Pokemon Reshiram.

Official Artwork for N with a Legendary Pokemon Zekrom.

In relation to that, the game does NOT offer the player the choice to just lay down their Pokeballs and finish up. To progress through the story the player must continue to utilise their Pokemon and defeat other Pokemon through battle. Although the story does end up showing that Team Plasma were working in their own interests, not for the Pokemon’s.

It might be a bit of a loose comparison but I found it interesting to use the term Ludonarrative Dissonance in relation to a Pokemon game of all things. I wouldn’t normally say Pokemon Games are huge narrative driven games but Black and White certainly made me question some things.

To sum up, the term Ludonarrative Dissonance is an interesting and important one when it comes to Video Games critique and journalism. As Hocking mentions in his post “BioShock is not our Citizen Kane. But it does…show us how close we are to achieving that milestone” and I think that’s an interesting statement. In recent years the matching of Gameplay and Narrative has certainly begun to come more clear with less of this Ludonarrative Dissonance and a much more clear focus of themes and player choice.

That’s it for me this week! I hope you enjoyed reading and I’ll see you next week!

Thanks for reading!

– Nathan “Naff” Hibbert