Diegesis in Video Games refers to the Narrative elements within the game itself. There are then Intra-Diegetic and Extra-Diegetic. Intra-Diegetic refers to elements of the game that belong to the game’s world, examples of this are the Characters themselves, the environment and items, these are things that can be perceived by the Game’s Characters. Whereas Extra-Diegetic refers to the elements of the game that don’t belong to the world itself, such as menus, music and the HUD, these are things that can NOT be perceived by the Game’s Characters. These elements do not always stick within these boundaries though.

I stumbled across an article by Gregory Weir on Gamasutra.com from November 2008 exploring the Diegesis of the LucasArts’ game Grim Fandango, the article itself can be found here. This week I’ll be posting a response to said article.

Weir begins the article by mentioning the split in the world inhabited by a Game’s Characters and the world that is shown to the player. The way this is shown is by using Intra-Diegetic and Extra-Diegetic elements. Weir explains the term Diegesis within a Film context by mentioning Music specifically. If a character directly plays a certain song, be that via instrument or player of some sort, then that is Diegetic music. Whereas if it is moreso background music then that would be non-diegetic.

Weir goes on to mention how Diegesis works in Video Games. As I previously stated there are many different attributes of Games that can be shown as Diegetic. It is these attributes that contribute to, or take away from, the immersion that any developer may be trying to achieve.

Many games use Diegesis to add to this immersion factor. The ‘Fallout Series’ features an item known as a ‘Pip Boy’ a device in the game used to manage inventory and character traits, now this is only Diegetic because the character raises their arm when the player presses the Inventory button. It is this acknowledgement that makes the action Diegetic. Much like in ‘Goldeneye’ for the N64, Bond raises his arm to look at his watch which then acts as a pause menu among other things. Both of theses are examples of Diegetic attributes.

Another example is within the Blizzard game ‘Overwatch’. Characters that use guns sometimes have visual markers on their guns that show their current ammo count. While this isn’t a necessary addition due to the game’s HUD also having a more traditional ammo count featured in the bottom right hand corner, it goes to show the character’s personalities more than otherwise shown. With ‘Overwatch’ being an FPS game the player does not see much of the character they are playing besides their hands and their weapon for the most part. An example can be seen below with Sombra’s weapon. Most skins feature a hexadecimal counter that represents her current ammo count, this plays into her character trait being a hacker of sorts.

The “3C” at the top of the gun means 60 as a Hexadecimal

The “28” at the top of the gun means 40 as a Hexadecimal

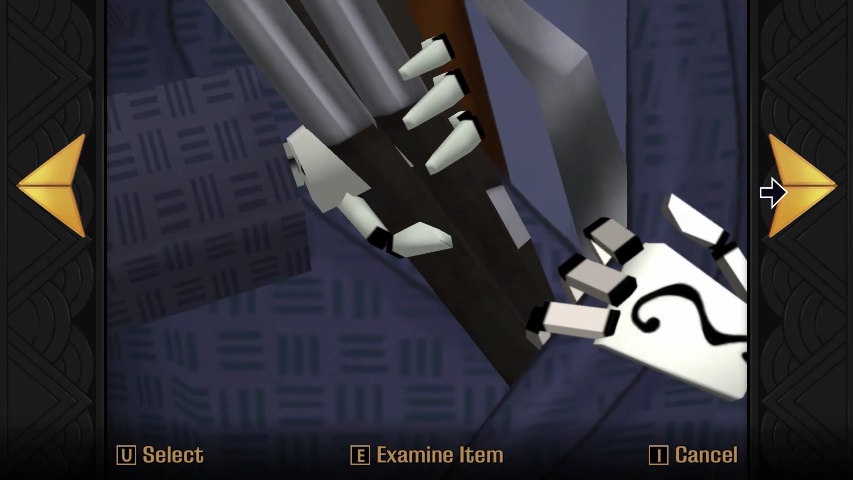

In the case of LucasArts’ ‘Grim Fandango’, the main example of Diegetic usage is the inventory. Weir writes that the player character, Manny, will individually pull any given item out of his coat as the player goes through the inventory. Manny will put each one away as well before pulling out the next. This is a great example of Diegetic techniques as it involves the player character in an event that normally only involves the player.

Diegesis is not always a constant plus in Video Games. To stick with Grim Fandango for a minute, the inventory system that is present isn’t the most user friendly. Weir also touches on the fact that during some parts of the game Manny’s inventory may be packed to the brim with items so having to sort through every single one individually is awfully time consuming and is not very ergonomic for the player. It is also more than likely working against it’s intended purpose of bringing the player into the Game’s World and is instead pushing them away somewhat.

Another example of Diegesis working against the player is in the most recent ‘Animal Crossing’ release. ‘Animal Crossing: New Horizons” features both an inventory and crafting system. At maximum the player can have 40 different items in their inventory and any number of items in their house storage. But when it comes to crafting the player MUST have the required items in their inventory to craft anything. This, again, works against the player if they are crafting within their own home. It just makes sense from a gameplay point of view for a crafting area within the same place as the storage to be able to interact with said storage. This would remove the middle man, this being the player action of removing things from storage to craft, completely, allowing for a more streamlined experience.

As I mentioned earlier, Diegesis is a method of bringing the player closer to the game, to immerse the player in the game’s world. To bring the player into that “Magic Circle”. Weir speaks about how the developer can remove non-Diegetic elements to “make it easier for the player to lose herself in the game”. That being said, Weir also prods into the idea that there can be high-level immersion and player investment in a game that is mostly non-Diegetic.

In the case of ‘Grim Fandango’, the game definitely would have been more player-friendly had it utilised a more conventional inventory system. Weir can be quoted saying “In this case, immersion would probably be restored by using an easier but less Diegetic inventory system. This would undermine Grim Fandango’s goal of creating a cinematic experience, but it would make the game less frustrating and easier to use.”.

Diegesis is an important thing for Developers to consider when it comes to creating a Game as a user experience. Especially the thought of when it is best to use it, should this attribute be Diegetic or non-Diegetic? That is a question that the Developer should be thinking about.

That’s it for this article, thank you once again for reading! I’ll be back soon with another article about Procedural Generation in Video Games.

Thanks again for Reading!

– Nathan “Naff” Hibbert